Resveratrol and the French Paradox

18 Mar 2022A few years ago, you might have read that red wine can help protect against heart disease, an exciting development for wine lovers worldwide. In the years since, however, there have been many conflicting reports on the health benefits of red wine. As a plant biologist, what interested me most when reading these articles was, of course, the plant itself. What exactly are grapes making that is so good for humans when consumed? And are there really enough of these health-promoting compounds in red wine to counteract the adverse effects of alcohol? Because, sadly, yes alcohol is bad for humans. (https://www.who.int/health-topics/alcohol).

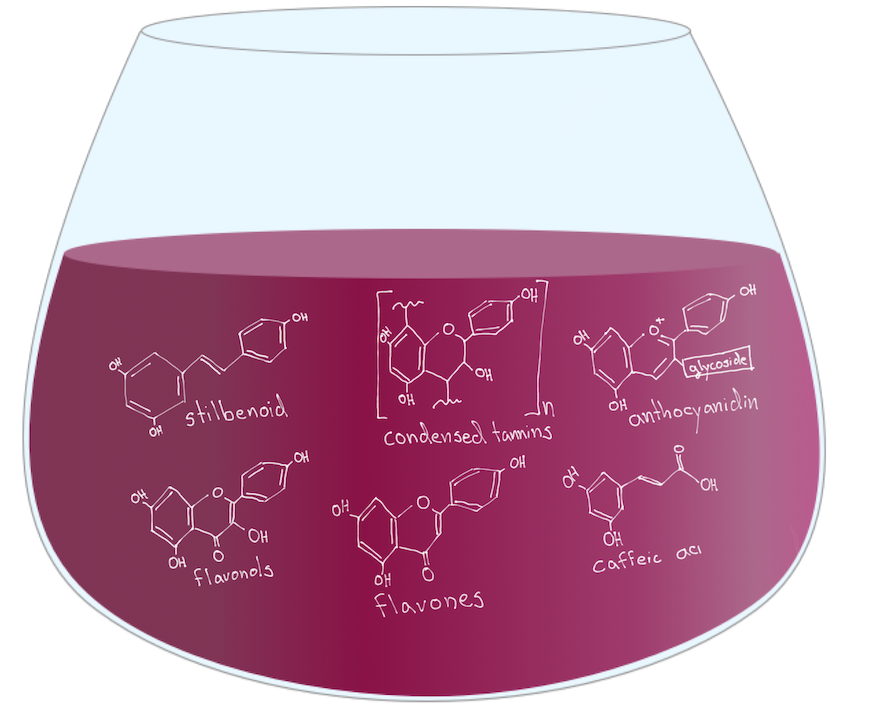

The short answer to my first question is phenolics. Grapes produce an abundance of phenolic compounds in their skins which help to protect their seeds from insects, UV radiation, and infection by pathogens. Unlike white wine, when red wine is made, the skins are included in the fermentation process. This means that all phenolic compounds in the skin carry through to the final product. What’s more, during the fermentation, phenolic compounds are extracted from the grape skin and seed coat, meaning that there is considerably more phenolic content in wine than in a glass of grape juice.

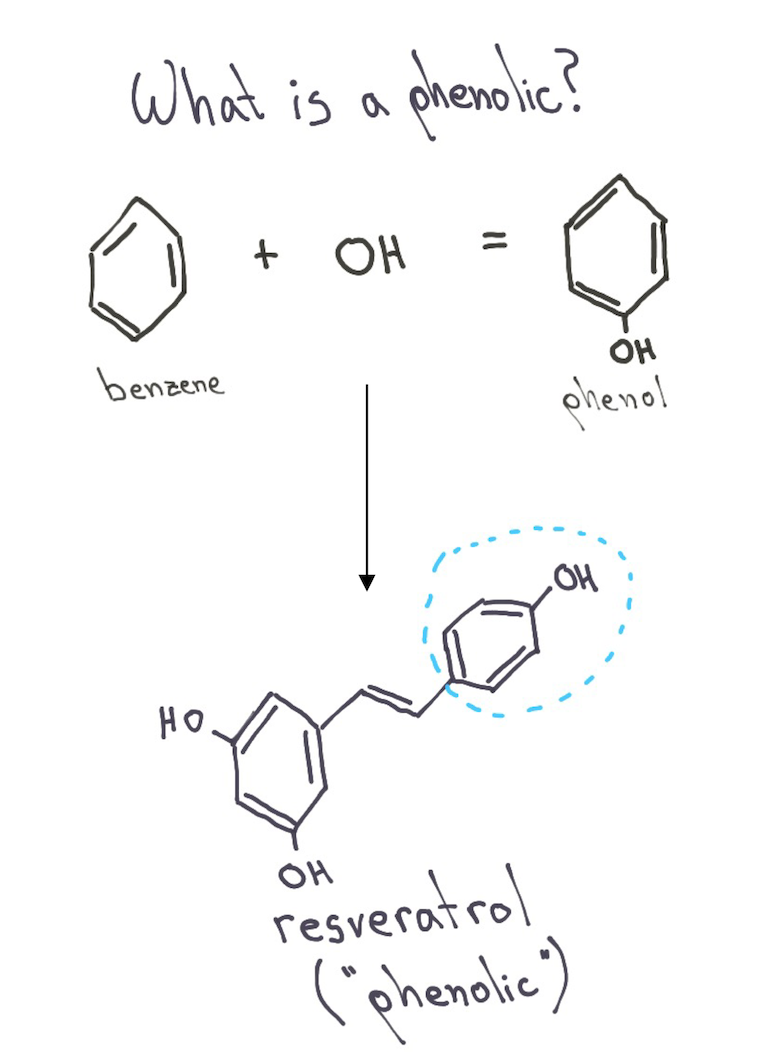

In a glass of red wine, you will find phenolics like condensed tannins, anthocyanidins, flavones, flavonols and stilbenes and while these compounds might look very complicated, you only need to focus on one thing: the phenolic component. These compounds all contain some form of an aromatic ring attached to at least one OH group, making them part of the chemical class termed “phenolics”.

Phenolics are essential to plants because, first and foremost, they help to protect against the adverse effects of UV radiation. They also help mitigate the oxidative damage inside plant cells that can arise from drought stress, and other abiotic (non-living) stressors. This is what makes them antioxidants. In fact, it is widely believed that phenolics were essential to the evolution of land plants, by allowing their sensitive photosynthesizing cells to withstand UV radiation without the protection of water provided to their aquatic ancestors (Lattanzio et al. 2010).

Phenolics can also play other more specialized roles in a plant. For example, the anthocyanidins in red grapes are what give the skin a reddish-purple color. Condensed tannins, on the other hand, are very important in deterring insects and pests. Condensed tannins give wine a slightly bitter taste, making your tongue feel dry as you drink.

Resveratrol is a phenolic found in high amounts in grape skin, and subsequently red wine. The compound has garnered significant interest for its ability to act as an anticancer agent by preventing cell proliferation. It is also reported to promote heart health, protect against neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer′s, Huntington′s, and Parkinson′s diseases as well as act as an anti-inflammatory agent (Salehi et al. 2018).

So why is resveratrol such a potent therapeutic? One of the main reasons is that resveratrol is a powerful antioxidant when compared to many other plant phenolics. In fact, resveratrol is such a powerful antioxidant that it was once proposed as the answer to the “French Paradox, and could account for the good heart health of the French despite their consumption of more butter, cheese, and pork than their North American counterparts (Catalgol et al. 2012).

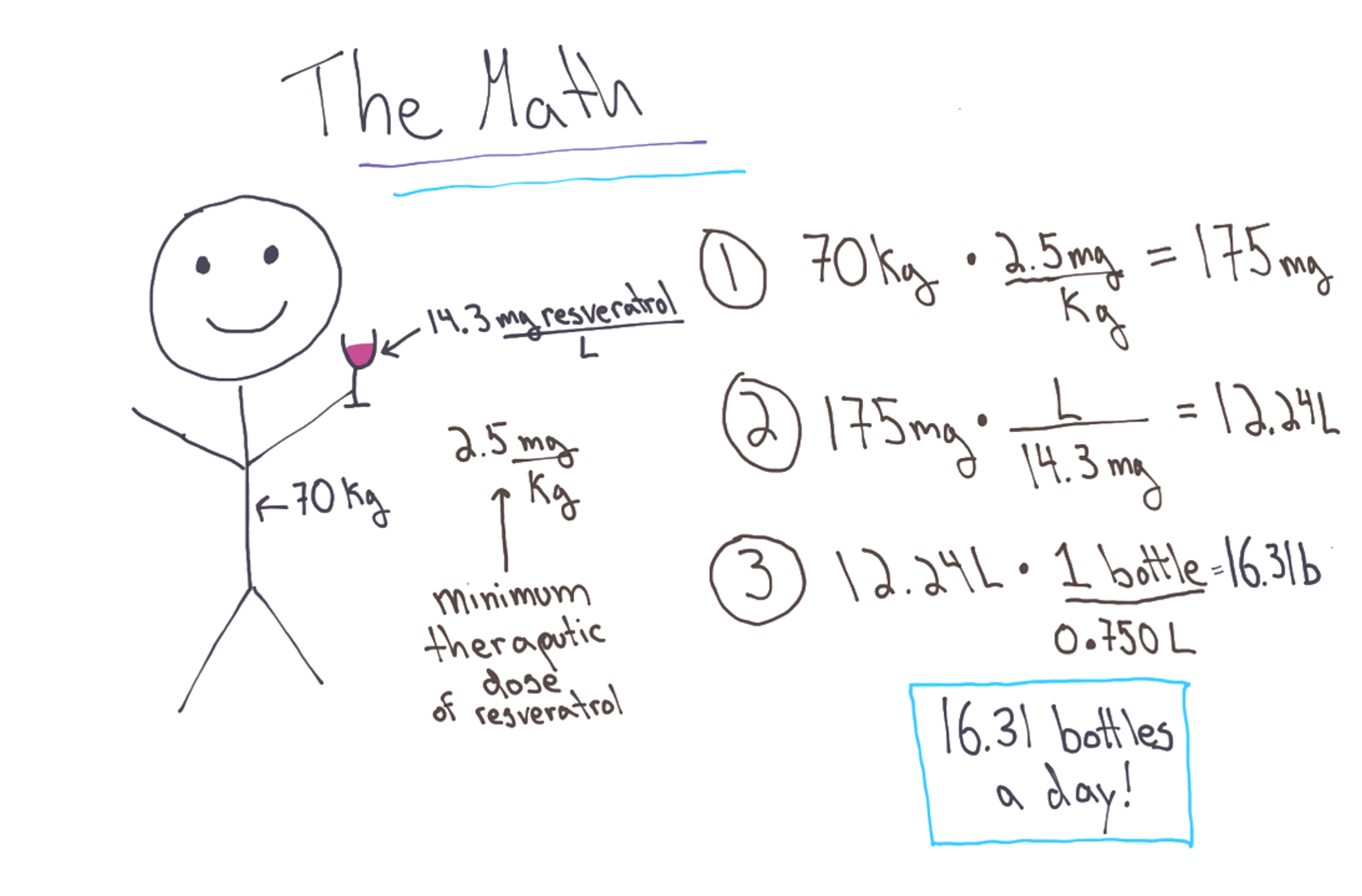

Unfortunately, one of the major problems with this hypothesis has to do with the therapeutic dose of resveratrol compared to the levels present in wine. Only around 70 plant species produce resveratrol, including grapevines, peanuts, and tomatoes. Of these plant species, grapes produce the highest amounts of resveratrol, especially in their skins. Red wines contain between 0.1 – 14.3 mg/L (Dudley et al. 2008), and most medical studies have shown that for resveratrol to be administered at a therapeutic dose, it must be at least 2.5 mg/kg (Mukherjee 2010). Meaning the average North American would need to consume at least 16 bottles of wine a day to start benefiting from resveratrol. Unfortunately, I think this is a dietary regime most doctors would recommend against.

Of course, you can always buy resveratrol supplements over the counter. These supplements are typically produced using genetically engineered yeast strains, the same type of yeast used for thousands of years in baking, beer brewing, and, ironically, winemaking. More recently, there has been some interest in finding ways to increase the amount of resveratrol made by grapes naturally. Researchers have found that when grapevines are subjected to stresses such as UV radiation, pathogen challenge, or even sonication, they upregulate the genes required to make resveratrol and increase the production by up to 2000 fold in some cases (Hassan and Bae 2016). So, there may be resveratrol enriched wines coming to a store near you!

Either way, whether you choose to drink a glass of red wine with dinner, snack on some grapes or take a supplement, resveratrol is one of the many wonderful plant compounds that help to keep us healthy and our cells free of oxidative stress!

Bonus Reading:

Catalgol, B., Batirel, S., Taga, Y. and Ozer, N.K., 2012. Resveratrol: French paradox revisited. Frontiers in pharmacology, 3, p.141.

Dudley, J., Das, S., Mukherjee, S. and Das, D.K., 2009. RETRACTED: Resveratrol, a unique phytoalexin present in red wine, delivers either survival signal or death signal to the ischemic myocardium depending on dose.

Lattanzio, V., Cardinali, A. and Linsalata, V., 2012. Plant phenolics: a biochemical and physiological perspective. Recent advances in polyphenols research. Chapter 1

Mukherjee, S., Dudley, J.I. and Das, D.K., 2010. Dose-dependency of resveratrol in providing health benefits. Dose-response, 8(4), pp.dose-response.

Salehi, B., Mishra, A.P., Nigam, M., Sener, B., Kilic, M., Sharifi-Rad, M., Fokou, P.V.T., Martins, N. and Sharifi-Rad, J., 2018. Resveratrol: A double-edged sword in health benefits. Biomedicines, 6(3), p.91